A tsunami of COGS

Is the Uber era of AI coming to an end?

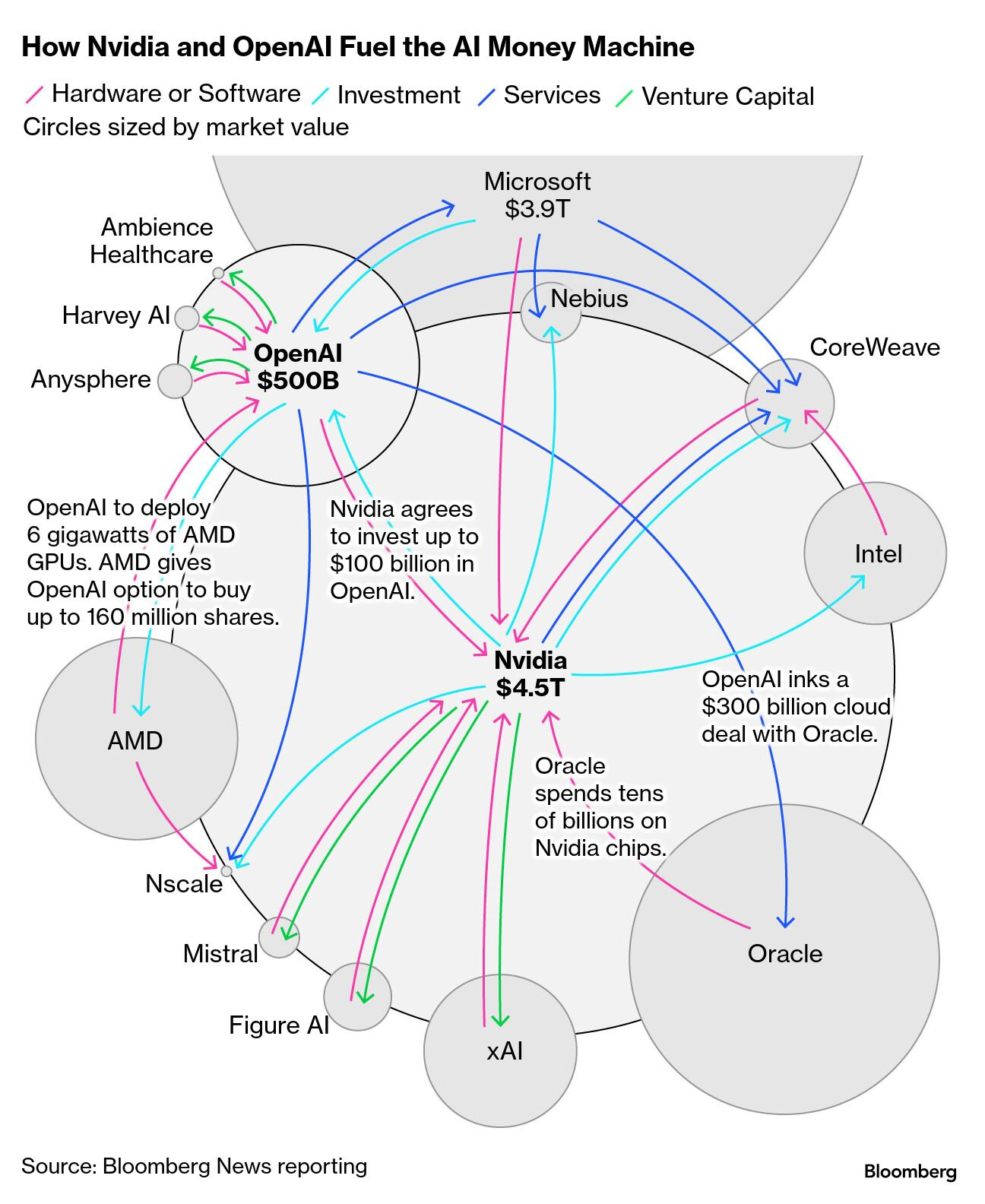

The AI industry is in correction mode. Last week Nvidia reported its earnings and the world was holding its breath. If they miss, it is so over. If they crush it, we are so back. In the end, earnings beat expectations, but the stock slid anyway after an initial bump. Many things in the AI boom smell bad. The way money fuels the investment spree is quite questionable and it has become a meme, with the same $1T investment check moving hands among a small set of participants. We can call this “vendor financing”, but it is not a great look.

In my opinion the players more at risk here are the hyperscalers like Microsoft, Amazon and Oracle, and the neocloud players like Nebius and CoreWeave. They are in between the providers of chips like Nvidia and the buyers of compute like OpenAI. They really have no choice other than buying real chips from Nvidia, and hoping that there will be sustainable demand (read: revenue > COGS) from buyers of compute so that they can honor those commitments. If not, the buyers of compute will walk away, resizing their commitments (or going bankrupt), Nvidia already sold those GPUs, and the hyperscalers are left with billions and gigawatts of unused capacity that depreciate very quickly due to the short GPU lifespan.

The sentiment about the (un)sustainability of the AI industry is growing. Sam Altman lost his cool on a podcast when the host asked how OpenAI, with $13B in revenue, can make $1.4T of spending commitments with AMD, Nvidia, Microsoft etc. The nervous and annoyed response did not pass unnoticed, and it was interpreted as a sign that there is not enough revenue coming to support this level of investment. A few days later, the OpenAI CFO Sarah Friar made a comment that sounded like the company was seeking support from the federal government to make it easier to finance sizable investments in AI compute capacity, using the words “backstop” and “guarantee”. This comment was later retracted and clarified by Friar and Altman, but it was not a great week for OpenAI.

The problem is not (only) revenue, and whether $13B in revenue is enough to support $1.4T in spending commitments ... it is also margins. AI is amazing, but maybe it is too cheap to be true. It seems that we are in the early Uber days where calling an Uber was so much cheaper than a taxi that you might even question whether owning a car makes financial sense.

Take GitHub Copilot for example. The Pro SKU is $10 a month and comes with an allowance of 300 requests. Additional requests are priced at $0.04 each, so 300 × $0.04 = $12. GitHub is selling $12 in retail value for $10. We do not know the margins on those $0.04, but it is not excluded that they are negative, which would push the true retail value even higher for the same $10.

Overall it seems that all the challengers, like OpenAI, Anthropic, Cursor, are subsidizing demand with negative margins. Google was surprised by the AI boom and it took a while for it to get its act together, but it is now coming back strong, launching Gemini 3 and also an IDE. Differently from the challengers, Google’s pockets are full thanks to other highly profitable revenue streams (search, YouTube, GCP), and they are better positioned to play the negative margin game.

If the challengers do not want to drown in a tsunami of COGS, something has to change. Let’s unpack this.

AI is both SaaS and PaaS, for the consumer market and the enterprise market. AI players offer SaaS applications like ChatGPT, Sora, Codex, Cloud Code etc., but also PaaS in terms of LLM APIs and traditional storage and compute.

The standard pricing model for SaaS is a subscription, both in the consumer segment and the enterprise segment. A subscription is basically an entitlement to consume a certain amount of resources. In the case of a consumer SaaS like Netflix the entitlement is the entire movie catalog. For tools like ChatGPT the entitlement differs depending on the model used. If it is very cheap and a few generations behind, the entitlement can even be without limit (i.e. too cheap to meter). If the model is more expensive (e.g. reasoning models) or frontier, the entitlement is capped to a certain amount of requests. Treating user requests without considering the model used can be a disaster, like Augment Code experienced:

The user message model also isn’t sustainable for Augment Code as a business. For example, over the last 30 days, a user on our $250 Max plan has issued 335 requests per hour, every hour, for 30 days, and is approaching $15,000 per month in cost to Augment Code. This sort of use isn’t inherently bad, but as a business, we have to price our service in accordance with our costs.

The subscription/entitlement model works best if COGS grow slower than the user base. Netflix is the best example. Their COGS is the catalog of movies and TV series. The more users they acquire, the more content they need to have in their catalog to satisfy the diversity of preferences that comes with a growing user base. However, the same movie can be watched by multiple users, so COGS grows slower than the user base.

However, in AI products COGS are tokens. Each user request consumes brand new and unique tokens required by the LLM. There is no sublinearity of growth here. The more users you have, the more COGS. That is why AI SaaS are addressing this with usage-based pricing, which is becoming more and more common1.

For now it is not pure usage-based pricing. It is still a combination of a monthly payment upfront that comes with a certain entitlement, plus a mechanism to go over that if needed. This is typically the model for enterprise SaaS, where enterprises buy “seats” for their users and pay “overages” for anything extra.

Pure usage-based pricing is more like PaaS per enterprises, aka cloud bills, where you pay only for the storage and compute usage, nothing more, nothing less. This would require a big mind shift in the consumer market, where people are used to pay for digital services with a fixed monthly payment like Netflix (with frequent price increases, I have to say), not like a utility bill.

Pure usage-based pricing would allow AI SaaS to pass COGS + margin to users without playing any risky entitlement game, and it seems the easiest way out. End users will most likely see higher prices, or will have to reduce consumption of AI products, which will be hard because we have become hooked to it.

I am not sure AI SaaS have a lot of other choices to reduce COGS. I see some efforts to do token optimisation, for example with the introduction of “auto-mode” where the user does not need to pick a model but the SaaS itself does that, trying to use the cheaper models when possible. I also wonder whether token reusability is possible. AI products feel very personalised and tailored to the user prompt, but I guess there is a decent overlap in what users are prompting (at least in the AI chatbot space), so maybe there is space to “cache” prompts like with search and reuse previous answers.

In any case, the AI industry is at a critical point. Either they keep burning money to provide amazing products that are too cheap to be true, or they find a way to transfer those COGS to end users while retaining them.

Do you like this post? Of course you do. Share it on Twitter/X, LinkedIn and HackerNews